Founded in 1997, Casa Delfin Sonriente remains one of the most sought out B&B’s for surfers and the like. This destination villa caters to surfers, outdoor adventurers, foodies, and most recently spa enthusiasts. Casa Delfin Sonriente is nestled in the town of Troncones on the Pacific Ocean side of Southern Mexico.

LAS POSADAS-MEXICO - CHRISTMAS AROUND THE WORLD

Las Posadas is a nine-day Navidad (Christmas) celebration with origins

in Spain. Las Posadas are now celebrated mainly in Mexico and Guatemala.

Posada is the Spanish word for "lodging", or "accommodation.” It is

written in the plural because the celebration spans a period of several

nights.

In Mexico, the Christmas holidays begin unofficially with the saint's day of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The festivities are in full swing with the beginning of the posadas — celebrated each evening from December 16 to 24. They are, in fact, a novenario — nine days of religious observance based on the nine months that Maria carried Jesus in her womb.

The posadas re-enact Mary and Joseph's cold and difficult journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem in search of shelter or lodging.

Traditionally, a party is held each night in a neighborhood home. At dusk, guests gather outside the house with children dressed as shepherds, angels and sometimes, Mary and Joseph. An angel leads the procession, followed by Mary and Joseph or by guests carrying their images. The adults follow, carrying lighted candles.

Every home has a nativity scene and the hosts of the Posada act as the innkeepers. The neighborhood children and adults are the pilgrims (peregrinos). The "pilgrims" sing a traditional song asking for shelter, and the hosts sing a reply. All the pilgrims carry small, lit candles in their hands. Four people carry small statues of Joseph leading a donkey, on which Mary is riding.

The head of the procession will have a candle inside a paper lamp shade. At each house, the resident responds by refusing lodging until finally the weary travelers reach the designated site for the party, where Mary and Joseph are finally recognized and allowed to enter. Once the "innkeepers" let them in, the guests come into the home and kneel around the Nativity scene to pray (typically, the Rosary). The “innkeepers” offer the “peregrinos” and their guests hot cider, fried rosette cookies known as buñuelos, steaming hot tamales and other festive foods.

The party ends with a piñata in the shape of the Christmas star. Inside the piñata, there are cnadies, fruit and other goodies for the children.

The last posada, held on December 24, is followed by midnight mass, a tradition that lives on in countless Mexican towns and cities.

Many Latin-American countries continue to celebrate this holiday with very few changes to the tradition. In some places, the final location may be a church instead of a home. Individuals may actually play the various parts of Mary (María) and Joseph with the expectant mother riding a real donkey (burro), with attendants such as angels and shepherds acquired along the way, or the pilgrims may carry images of the holy personages instead. At the end of the long journey, there will be Christmas carols (villancicos).

In Mexico, the Christmas holidays begin unofficially with the saint's day of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The festivities are in full swing with the beginning of the posadas — celebrated each evening from December 16 to 24. They are, in fact, a novenario — nine days of religious observance based on the nine months that Maria carried Jesus in her womb.

The posadas re-enact Mary and Joseph's cold and difficult journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem in search of shelter or lodging.

Traditionally, a party is held each night in a neighborhood home. At dusk, guests gather outside the house with children dressed as shepherds, angels and sometimes, Mary and Joseph. An angel leads the procession, followed by Mary and Joseph or by guests carrying their images. The adults follow, carrying lighted candles.

Every home has a nativity scene and the hosts of the Posada act as the innkeepers. The neighborhood children and adults are the pilgrims (peregrinos). The "pilgrims" sing a traditional song asking for shelter, and the hosts sing a reply. All the pilgrims carry small, lit candles in their hands. Four people carry small statues of Joseph leading a donkey, on which Mary is riding.

The head of the procession will have a candle inside a paper lamp shade. At each house, the resident responds by refusing lodging until finally the weary travelers reach the designated site for the party, where Mary and Joseph are finally recognized and allowed to enter. Once the "innkeepers" let them in, the guests come into the home and kneel around the Nativity scene to pray (typically, the Rosary). The “innkeepers” offer the “peregrinos” and their guests hot cider, fried rosette cookies known as buñuelos, steaming hot tamales and other festive foods.

The party ends with a piñata in the shape of the Christmas star. Inside the piñata, there are cnadies, fruit and other goodies for the children.

The last posada, held on December 24, is followed by midnight mass, a tradition that lives on in countless Mexican towns and cities.

Many Latin-American countries continue to celebrate this holiday with very few changes to the tradition. In some places, the final location may be a church instead of a home. Individuals may actually play the various parts of Mary (María) and Joseph with the expectant mother riding a real donkey (burro), with attendants such as angels and shepherds acquired along the way, or the pilgrims may carry images of the holy personages instead. At the end of the long journey, there will be Christmas carols (villancicos).

Summer Rates in Winter!

25% Discount - Summer rates extended until

December 15th! $85 per night for a suite/$64 per night for a private

room, breakfast included.

Mexican kitchen: a gourmet guide to food in Mexico

Read on for a brief (but mouth-watering) introduction to Mexican cuisine from the latest edition of Lonely Planet’s Mexico guide book.

What’s on the menu?

Mexican cuisine has little to do with what’s served in Mexican restaurants outside the country. For many visitors their first experience with real Mexican food is a surprise – there are no big hats, no flavoured margaritas or cheese nachos on the menu. Authentic Mexican food is fresh, simple and, frequently, locally grown – and most likely, somebody’s mother will be running the kitchen.Mexican menus vary by region, but in most cases you can find food made with a few staples: corn, an array of dry and fresh chillies, and beans.

Contrary to popular belief, not all food in Mexico is spicy, at least not for the regular palate. Chillies are used as flavouring ingredients and to provide intensity in sauces, moles and pipiáns, and many appreciate their depth over their piquancy. But beware: many dishes do indeed have a kick, reaching daredevil levels in some cases. A good rule of thumb is that when chillies are cooked into dishes as sauces they tend to be on the mild side, but when they are prepared as salsas or relishes used as condiments, they can be really hot.

Other staples that give Mexican food its classic flavoring are spices like cinnamon, clove and cumin, and herbs such as thyme, oregano, and most importantly, cilantro (coriander) and epazote.

Epazote may be the unsung hero of Mexican cooking. This pungent-smelling herb (called pigweed or Jerusalem oak in the US) is used for flavouring beans, soups, stews and certain moles.

Eating on a whim

Antojitos are at the centre of Mexican cooking. The word antojo translates as ‘a whim, a sudden craving,’ but it’s not just a snack – you can have them as an entire meal, or a couple as appetizers (or yes, just one as a tentempíe, or ‘quick bite’). There are eight types of antojitos, all with the central component of corn masa (dough):- Tacos: the quintessential culinary fare in Mexico can be made of any cooked meat, fish or vegetable wrapped in a tortilla, with a dash of salsa and garnished with onion and cilantro.

- Quesadillas: fold a tortilla with cheese, heat it on a griddle and you have a quesadilla. (Queso means cheese.) In restaurants and street stalls they’re stuffed pockets made with raw corn masa that is lightly fried or griddled until crisp. They can be stuffed with chorizo (spicy sausage) and cheese, squash blossoms, mushrooms with garlic, chicharrón (fried pork fat), beans, stewed chicken or meat.

- Enchiladas: a group of three or four lightly fried tortillas filled with chicken, cheese or eggs and covered with a cooked salsa; usually a main dish.

- Tostadas: tortillas that have been baked or fried until they get crisp and are then cooled to hold a variety of toppings. Tostadas de pollo are a beautiful layering of beans, chicken, cream, shredded lettuce, onion, avocado and queso fresco (a fresh cheese).

- Sopes: small masa shells, two or three inches in diameter, that are shaped by hand and cooked on a griddle with a thin layer of beans, salsa and cheese; chorizo is also a common topping.

- Gorditas: round masa cakes that are baked until they puff. Sometimes gorditas are filled with a thin layer of fried black or pinto beans, or even fava beans.

- Chilaquiles: corn tortillas are cut in triangles and fried until crispy, then cooked in a tomatillo (chilaquiles verdes) or tomato salsa (chilaquiles rojos) to become soft, then topped with shredded cheese, sliced onions and Mexican crema. Typically served as breakfast.

- Tamales: made with masa mixed with lard, stuffed with stewed meat, fish or vegetables, wrapped and steamed. Every region in the country has its own, the most famous being the Oaxacan-style tamales with mole and wrapped in banana leaves and the Mexico City tamales with chicken and green tomatillo sauce wrapped in corn husks.

- Mauricio Velázquez de León

- Lonely Planet Author

Read more: http://www.lonelyplanet.com/mexico/travel-tips-and-articles/77547#ixzz2BpbYsxoc

Dia De Los Muertos/Day of the Dead

Dia De Los Muertos/Day of the Dead photo album

Visit our Facebook page to see an album of photos celebrating Dia De Los Muertos/Day of the Dead.

Visit our Facebook page to see an album of photos celebrating Dia De Los Muertos/Day of the Dead.

A Traveler's Narrative of Troncones (from Pique Magazine, British Columbia)

- Photo by Kevin Zemani, flickr.com/photos/xbleh

Somewhere near the middle of the Pacific side of Mexico

lies a beachside village that has more or less escaped the attention of

large scale resort developers. It draws a certain breed of visitor, even

converting some to part-time residents. For those with a sense of

adventure and a desire to partake in the daily life of an authentic

Mexican community, Troncones is probably the beach destination you have

been looking for.

We found it the best way — by word of mouth. We had spent two nights in Zihuatanejo before the call to move came upon us thanks mostly to the fact that the harbour town had no waves to speak of and we were looking for surf. We would have spent much more time there if decent waves were close. The town has a rich history of pirates and conquistadores, and the warm hospitality we received from the community was second to none. But being a harbour town, the only waves inside the bay were quick closeouts that rarely went over the head.

Despite no surf in the town, there were a few random surf shops nearby, a sure sign that there were enough waves in the area to keep the locals stoked. One of the shop clerks was more than happy to share knowledge about nearby breaks, especially after we make a few purchases. He mentioned Troncones and gave the number of his friend Luis who owned a set of bungalows on the beach. All that sounded good enough to set a course to the village.

The only information we had was which bus to catch from the central depot. We told the driver to let us off at the stop toward Troncones, and hoped that he would remember to tell us. What ensued was probably the most fun I've ever had on a bus. The only parts on the bus less than 20 years old were the CD player, a 10" subwoofer, and a half dozen 6x9 speakers. For an hour the roof of the bus resonated with Reggaeton and Mariachi-Moderna, as well as the usual top 40 crowd-pleasers. All the while screaming down the road as fast as the old bus can handle — though we had our doubts about safety a few times along the way.

Finally the bus driver stopped and signaled to the only gringos aboard, us, that this was where our trip with him ended. We transferred to a van to take us to the coast. The van stopped at a village with plenty to offer to a tourist. English signs pointed to several mini-resorts, each one with no more than 20-30 beds. Of course, some were nicer than others with private pools and cantinas.

Luis' place ended up being everything we would need — a half dozen bungalows each with a double bed, outdoor shower, a communal kitchen, and enough hammocks on the property for everyone to have a siesta in peace. More importantly the front yard of the property was an immaculate beach with eight-foot barrelling breaks thundering offshore. This was exactly what we were looking for, and had it been featured in a guidebook, the hostel crowd probably would have overrun this place long ago.

Troncones has two main streets: the one that led into town from the main highway, and another that intersects that road and parallels the beach. The road along the beach boasted all the tourist activity. The local residents lived in the nearby hills but would congregate near the intersection, choosing between a community volleyball court, skate park, and pool tables for afternoon social activities.

Back at the bungalows we met three couples: one from Vail, one from Fernie, and one from China Peak. All had the same intention as we Whistlerites: escape the dead season doldrums for a few weeks, wait for the snow, and get some final shots of Vitamin D before the long winter ahead. The couple from Vail had rented a car and offered to take us along while they explored the local surf spots. Over the next week we went north to El Rancho and south to Playa Linda, rejoicing in perfect, fun waves that we had all to ourselves, meeting the random local every so often. The vibe behind the breakers was very relaxed, without the hint of possessiveness found north of the border where the waves are much more crowded.

At night a local family would open up their carport as a restaurant, and for less than $3 we fed ourselves until, stuffed on authentic home-cooked Mexican food, we trundled back to our bungalows.

Troncones might not be for everyone, but for those looking for an active vacation where you live the simple, unpretentious life of a beachside Mexican, then leave your worries at home and enjoy the opposite definition of "all-inclusive vacation."

We found it the best way — by word of mouth. We had spent two nights in Zihuatanejo before the call to move came upon us thanks mostly to the fact that the harbour town had no waves to speak of and we were looking for surf. We would have spent much more time there if decent waves were close. The town has a rich history of pirates and conquistadores, and the warm hospitality we received from the community was second to none. But being a harbour town, the only waves inside the bay were quick closeouts that rarely went over the head.

Despite no surf in the town, there were a few random surf shops nearby, a sure sign that there were enough waves in the area to keep the locals stoked. One of the shop clerks was more than happy to share knowledge about nearby breaks, especially after we make a few purchases. He mentioned Troncones and gave the number of his friend Luis who owned a set of bungalows on the beach. All that sounded good enough to set a course to the village.

The only information we had was which bus to catch from the central depot. We told the driver to let us off at the stop toward Troncones, and hoped that he would remember to tell us. What ensued was probably the most fun I've ever had on a bus. The only parts on the bus less than 20 years old were the CD player, a 10" subwoofer, and a half dozen 6x9 speakers. For an hour the roof of the bus resonated with Reggaeton and Mariachi-Moderna, as well as the usual top 40 crowd-pleasers. All the while screaming down the road as fast as the old bus can handle — though we had our doubts about safety a few times along the way.

Finally the bus driver stopped and signaled to the only gringos aboard, us, that this was where our trip with him ended. We transferred to a van to take us to the coast. The van stopped at a village with plenty to offer to a tourist. English signs pointed to several mini-resorts, each one with no more than 20-30 beds. Of course, some were nicer than others with private pools and cantinas.

Luis' place ended up being everything we would need — a half dozen bungalows each with a double bed, outdoor shower, a communal kitchen, and enough hammocks on the property for everyone to have a siesta in peace. More importantly the front yard of the property was an immaculate beach with eight-foot barrelling breaks thundering offshore. This was exactly what we were looking for, and had it been featured in a guidebook, the hostel crowd probably would have overrun this place long ago.

Troncones has two main streets: the one that led into town from the main highway, and another that intersects that road and parallels the beach. The road along the beach boasted all the tourist activity. The local residents lived in the nearby hills but would congregate near the intersection, choosing between a community volleyball court, skate park, and pool tables for afternoon social activities.

Back at the bungalows we met three couples: one from Vail, one from Fernie, and one from China Peak. All had the same intention as we Whistlerites: escape the dead season doldrums for a few weeks, wait for the snow, and get some final shots of Vitamin D before the long winter ahead. The couple from Vail had rented a car and offered to take us along while they explored the local surf spots. Over the next week we went north to El Rancho and south to Playa Linda, rejoicing in perfect, fun waves that we had all to ourselves, meeting the random local every so often. The vibe behind the breakers was very relaxed, without the hint of possessiveness found north of the border where the waves are much more crowded.

At night a local family would open up their carport as a restaurant, and for less than $3 we fed ourselves until, stuffed on authentic home-cooked Mexican food, we trundled back to our bungalows.

Troncones might not be for everyone, but for those looking for an active vacation where you live the simple, unpretentious life of a beachside Mexican, then leave your worries at home and enjoy the opposite definition of "all-inclusive vacation."

Kayaking in Troncones

Kayaking is one of the many popular activities

available during your stay in Troncones. We've created a flyer to

promote Casa Delfin Sonriente and the wide range of recreational

activities in the area. We'd appreciate it if you could distribute

it to your friends, family and acquaintances and don't forget to tell

them to friend our Facebook page to keep posted on the latest news from

this popular outdoors enthusiast''s destination.

Cry of Dolores Grito de Dolores Mexican Holiday September 15

Happy Independence Day Mexico! Sep 15

Source: Mexican YoYos by Tomas Castelazo

Mexican Coat of Arms

Source: Public domain

Cry of Dolores?

Are you familiar with the Mexican

holiday Cry of Dolores? Here we are with millions of Mexicans living

with us and yet this holiday is little known, unless of course you are Mexican. Each year at eleven on the evening of September 15 the President of Mexico rings the bell of the National Palace in Mexico City.

After the ringing of the bell, he repeats a cry based upon the "Grito

de Dolores", naming the heroes of the Mexican War of Independence and

ending with three shouts of ¡Viva Mexico!

Statue of Father Hildago, Dolores Mexico

Hildago

Source: Public domain

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

The Grito de Dolores

("Cry of Dolores") also known as El Grito de la Independencia ("Cry of

Independence"), was first shouted from the small town of Dolores, near

Guanajuato on September 16, 1810. This date marks the beginning of the

Mexican War of Independence and is the most important national holiday

observed in Mexico, akin to our 4th of July. The "shout" was

the cry of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Roman Catholic priest who

declared himself in open revolt against Spanish rule from the pulpit of

his church.

He encouraged his parishioners to join him and fight against the

Spanish Colonial rule. His flock joined him and he had an instant army

of some 600 followers. Hidalgo, shouted "Viva Mexico" and "Viva la

independencia!" These words have become famous, remembered and shouted

each year at the Independence Day celebrations. Hildago’s army

eventually swelled to over 80 thousand citizen soldiers. Hidalgo was no

saint, he gambled, fornicated, had children out of wedlock and didn't

believe in Hell, but he was a leader.

At first, the Criollos (wealthy Mexicans of Spanish descent), fought against the rebellion but in 1820, the approval of the Spanish Constitution, took privileges away from the Criollos, they switched sides so everyone fought together, including the Criollos, Mesizos (children born from the marriage of a Spaniard and an Indian), and Indians. Armed with clubs, knives, slings, and guns, this ragtag army marched on to Mexico City, fighting along the way. The first battle took place in Guanajuato between the Spanish soldiers and Hidalgo's followers. Hildago’s army conquered the town, killing the Spaniards. When they finally reached Mexico City, the revolutionary army delayed the attack and some of them even deserted the army. That same year, Father Hidalgo was captured, tried and executed but the revolution continued. Father Hidalgo's Grito de Delores (Cry of Delores) became the battle cry of the Mexican War of Independence. The Mexican revolution was fought for eleven long years but they finally won their freedom in 1821. There were millions of casualties in the revolution. During his trial, Hidalgo recanted his actions, perhaps foreseeing the destruction of lives and property to come.

At first, the Criollos (wealthy Mexicans of Spanish descent), fought against the rebellion but in 1820, the approval of the Spanish Constitution, took privileges away from the Criollos, they switched sides so everyone fought together, including the Criollos, Mesizos (children born from the marriage of a Spaniard and an Indian), and Indians. Armed with clubs, knives, slings, and guns, this ragtag army marched on to Mexico City, fighting along the way. The first battle took place in Guanajuato between the Spanish soldiers and Hidalgo's followers. Hildago’s army conquered the town, killing the Spaniards. When they finally reached Mexico City, the revolutionary army delayed the attack and some of them even deserted the army. That same year, Father Hidalgo was captured, tried and executed but the revolution continued. Father Hidalgo's Grito de Delores (Cry of Delores) became the battle cry of the Mexican War of Independence. The Mexican revolution was fought for eleven long years but they finally won their freedom in 1821. There were millions of casualties in the revolution. During his trial, Hidalgo recanted his actions, perhaps foreseeing the destruction of lives and property to come.

Act of independence 1821

Source: Public Domain

Mexican Flag

Declaration of Independence

After the death of Father Hidalgo, José María Morelos took the leadership of the revolutionary

army Under his leadership the cities of Oaxaca and Acapulco were

occupied. In 1813, the Congress of Chilpancingo was convened and on

November 6 of that year, the Congress signed the first official document

of independence. This document is the Mexican equivalent of our

Declaration of Independence, known as the

"Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America”:

“People of North America, South America and of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

I, Agustín de Iturbide, declare that the Viceroyalty of New Spain ceases to exist. The Empire of Mexico shall take it's place. I, Agustín de Iturbide, declare myself Emperador Agustín I. My first decree will be to establish a Senate from which the people may voice their opinions and pass legislation. But now we must celebrate the Empire day! From this day foreward September 6th shall be considered a national holiday. Empire day. This document shall now and always be known as the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America:

This created the first Mexican Empire which lasted a grand total of 18 months and followed by a long turbulent history, finally culminating in another revolution in 1910’

"Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America”:

“People of North America, South America and of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

I, Agustín de Iturbide, declare that the Viceroyalty of New Spain ceases to exist. The Empire of Mexico shall take it's place. I, Agustín de Iturbide, declare myself Emperador Agustín I. My first decree will be to establish a Senate from which the people may voice their opinions and pass legislation. But now we must celebrate the Empire day! From this day foreward September 6th shall be considered a national holiday. Empire day. This document shall now and always be known as the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America:

- "America is free and independent of Spain and all other nations, governments, or monarchies."

- The Catholic faith is the sole religion, and no others will be tolerated.

- Ministers of religion to survive on tithes and first fruits, with the people owing only devotion and offerings.

- Dogma as established by Church hierarchy: Pope, bishops, and priests.

- Sovereignty emanates from the people and is placed in a Supreme National Imperial Senate, made up of representatives from the provinces in equal numbers.

- Division of powers into appropriate executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

- Representatives to serve rotating four year terms.

- Adequate remuneration for representatives, not exceeding 8000 pesos.

- Jobs to be reserved for Americans only.

- No foreigners to be admitted, unless they are artisans capable of sharing their skills and free of all suspicion.

- Liberal government to replace tyranny, with the expulsion of the Spaniards.

- Laws should promote patriotism and industry, moderate opulence and idleness, and improve the lot and the education of the poor.

- Laws should apply to all, with no privileges.

- Laws to be drafted and discussed by as many wise men as possible.

- An end to slavery and discrimination based on castes.

- Homes and property to be inviolable.

- Torture shall not be permitted.

- 6th of September shall be celebrated as Empire day.

- Foreign troops should not enter the country and, if they do so to render assistance, may not approach the seat of government.

- No expeditions beyond the nation's borders to be permitted, particularly overseas expeditions; expeditions in the interior to spread the faith are allowed.

- An end to the payment of tributes; a tax of 5% or similar light amount to be levied.

- 16 September to be consecrated as the anniversary of the Emperor Agustín's coronation, our god sent saviour, and shall be celebrated.

This created the first Mexican Empire which lasted a grand total of 18 months and followed by a long turbulent history, finally culminating in another revolution in 1910’

Independence Day

http://www.flickr.com/photos/soaringbird/4995734303/sizes/z/in/photostream/By

http://www.flickr.com/photos/soaringbird/

Source: Flickr

mexican folk art Paper mach figures in Guanajuato Market, Mexico.

Intricate color patterns and color combinations are characteristic of

Mexican folk art, that often dwells in the magical, death, and

fantastic.

Important celebration in Mexico

Mexican Independence Day is as important a celebration in Mexico as the 4th of July is here and is bigger than Cinco de Mayo

or any other political holiday. This is party time in Mexico when

crowds of people gather in the town squares of cities, towns, and

villages. In the capital, Mexico City

is decorated with flags, flowers and lights of red, white, and green as

on the Mexican flag. The green, on the left side of the flag symbolizes

independence. White, in the middle of the flag symbolizes religion and

red on the right side of the flag symbolizes union.

Partiers throw confetti, make noise with whistles, horns and fireworks, and everywhere you see the national colors, red white and green. You can’t throw a party without food and Mexico is no exception from street vendors to private parties, feasting is the order of the day.! When the clock strikes eleven o'clock the crowd gets silent. On the last strike of eleven the president of Mexico steps out on the palace balcony, and rings the historic liberty bell that Father Hidalgo rang to call the people to church. Then the president gives the Grito de Delores. He shouts "Viva Mexico" "Viva la independencia" and the crowd echoes back. People all across Mexico do this at the same time.

Partiers throw confetti, make noise with whistles, horns and fireworks, and everywhere you see the national colors, red white and green. You can’t throw a party without food and Mexico is no exception from street vendors to private parties, feasting is the order of the day.! When the clock strikes eleven o'clock the crowd gets silent. On the last strike of eleven the president of Mexico steps out on the palace balcony, and rings the historic liberty bell that Father Hidalgo rang to call the people to church. Then the president gives the Grito de Delores. He shouts "Viva Mexico" "Viva la independencia" and the crowd echoes back. People all across Mexico do this at the same time.

The bell from the church at Dolores,

Close up of balcony where the president of Mexico gives the annual

Grito de Dolores on Independence day and the bell from the church at

Dolores, Guanajuato

Source: http://Thelmadatter

Colonial Mexico

Spanish Colonial Mexico was part of New Spain (formally called the Viceroyalty of New Spain)

which was established when the Spanish conquered the Aztec Empire in

1521. At its height, New Spain included much of North America south of Canada: all of present-day Mexico and Central America (except Panama), most of the United States west of the Mississippi

River including Texas plus Florida. Spanish rule in New Spain was a

caste system with power and wealth going to the people most closely

allied to Spain and related to Spanish blood. This led to resentment and

when Spain took privileges away from the Criollos, this sealed the fate

of Spanish Colonial rule. At the time, Spain was involved in the “The

Peninsular War,” the war between France and the allied powers of Spain,

the United Kingdom, and Portugal

for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. Spain

needed money to pay for these wars and they were extracting as much as

they could from the colonies, much like Britain was taxing Americans.

Romance of the stone

Six pieces of jade ware from Essence of Nature - Civilization of Ancient Jade in China and Mexico held in Beijing (Chinese works on the left, Mexican, right). |

These are two of civilization's oldest cultures and they share a common appreciation of jade. Now, the most exquisite pieces from ancient China and Mexico are sharing display space at the ongoing exhibition Essence of Nature - Civilization of Ancient Jade in China and Mexico.

Jointly organized by the Palace Museum and Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) and its National Council for Culture and the Arts, the exhibition was first hosted by the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico from March to June. It is now ready to solicit admiration from Chinese audience at the Palace Museum.

The exhibition also commemorates the 40th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and Mexico.

"It is definitely a feast for the eyes looking at such an exhibition at both countries' biggest and best museums," says the Palace Museum's director Shan Jixiang.

China chose 100 pieces and groups of jade ware from its collection of more than 30,000 jade collections, spanning a historical period of 8,000 years.

"The Palace Museum is probably the only museum that owns a jade collection ranging from the Neolithic Age to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)," says Xu Lin, associate researcher of the Palace Museum's Ancient Ware Department, who is also curating this exhibition.

"Many people think the Palace Museum focuses mainly on Ming (1368-1644) and Qing cultural relics. That's not true. About 80 percent of the exhibits provided by the Palace Museum this time came from before the Ming Dynasty."

Xu also mentions quite a number of jade items on display to the public for the first time.

The Jade Human and Beast Statue made during the Hongshan Culture of more than 5,000 years ago, for example, features a human with a cloud-shaped crown, grasping a stick with both hands, and standing on top of a bear-like beast.

"The complexity of its composition is unprecedented, which means it should be the highest-level jade ware known from the Hongshan Culture," Xu says.

The Jade Wizard is also a representative piece of the Hongshan Culture. It features a seated wizard figure wearing an animal hat. No other such relic has been found, which makes this a unique discovery.

The 100 pieces of jade from Mexico were carefully selected from museums throughout the whole country, and are drawn from a 3,000-year jade culture of widely known Central American civilizations such as the Maya and Olmeca.

The most eye-catching is a mosaic statue found in the heart of the Pyramid of the Moon in Teotihuacan, Mexico. The nude, asexual figure inlaid with various colored stones is believed to be a captive sacrificed for the pyramid during the period of the Teotihuacan Culture (AD 100-650).

Unlike the diverse colors found in Chinese jade, the Mexican stone is mostly green.

"Green stone worship is the most significant characteristic in Mexican jade culture," INAH project manager Miguel Baez says. "To ancient Mexicans, the green stone was the most valuable object, more valuable than gold."

"The green stones in ancient Mexico are from varied sources, quite different from the types of Chinese jade," Xu explains, adding that this is the biggest difference between the two jade cultures.

But she notes that the Chinese also worshipped green stones before the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), after which their enthusiasm gradually shifted to white jade, pointing out a Chinese turquoise necklace exhibited as evidence.

Burial jade, like the greenstone masks commonly used in Olmeca Culture (1400-400 BC) in Mexico, had relatively similar functions with Chinese jade burial masks found since the Western Zhou Period (1046-771 BC).

"Archaeological evidence shows there may have been interaction between China and Mexico in ancient times. We hope this exhibition can contribute to cultural exchanges in a wider context," Xu concludes.

Rainbow Over Troncones

Determined not to be shown up by Zihuatanejo, Troncones busted out her rainbow tonight as well.

From William Mertz, photographer.

From William Mertz, photographer.

DANCING WITH TURKEYS – Spirits Take Wing at a Small-town Mexican Wedding (part two of two)

One Man's Wonder

Reclaiming Curiosity in a "Ho-hum" World

from: onemanswonder.com

(CONTINUED FROM PART ONE)

(I'm attending a friend of a friend's wedding fiesta in Santiago

Tenango de Reyes, Pueblo. We've been invited to the home of the groom's

parents for an intimate family gathering just before the bigger party

begins.)

MY WORD!

For no particular reason I picked door number two and swept open the curtain. The young woman sitting on the toilet five feet in front of me scrambled to cover herself with a handful of toilet paper, but the damage was done. I exclaimed, backed gingerly away and waited nervously across the hall.

When she emerged, I gestured toward my heart with both hands and said earnestly: ¡Estoy tan embarasado! She seemed to accept my apology graciously, which must have been really hard for her, since—as I later found out—I'd just managed to forget about one of the most notorious false cognates in Spanish, and had exclaimed "I'm so very pregnant!"

I'd just managed to forget about one of the most notorious false cognates in Spanish, and had exclaimed "I'm so very pregnant!"

HOLY MOLE!

Eventually,

we all returned to the main party and sat down at one of the long

tables. As we made up for lost time with yet more bottles of tequila and

beer, the volunteer servers brought each of us a gigantic bowl of

chicken mole. (There must have been half a chicken in each bowl!) The

parents of the groom, sitting near us, were presented with even bigger

bowls—each the size of a large casserole, filled with what looked like

half a turkey!

The

parents of the groom, sitting near us, were presented with even bigger

bowls—each the size of a large casserole, filled with what looked like

half a turkey!The mole, with its complex blend of flavors, was very good, but none of us could even begin to finish such a portion. Apologizing, we were told not to worry; soon big plastic buckets were passed around and everyone just dumped in their leftovers. They offered us one of the buckets to take home with us, but we deflected the generosity to others whom we suspected would be far better able to use the food.

Now that it was dark, the mariachis wrapped up their gig and joined the party. Huge speakers and portable banks of equally loud colored lights had been installed right outside the dining area, under another big tarp. An endless flow of recorded popular and ranchero music started to blare, and people began to dance.

We'd heard somewhere about the wedding fiesta tradition of dancing with

goats or turkeys, which then would be slaughtered for dinner.

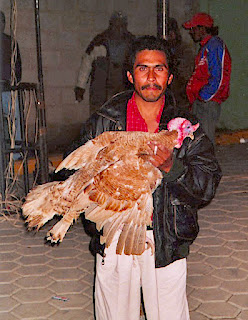

We'd heard somewhere about the wedding fiesta tradition of dancing with goats or turkeys, which then would be slaughtered for dinner. (This, I guessed, might be a remnant of Mayan or Aztec sacrificial offerings.) Sure enough, after an hour or so of dancing, the floor cleared and four older men (I suppose they were the village's elders) walked out, each holding a huge live guajolote (turkey) in his arms.

A simple, rhythmic music started and each man danced with his turkey. It was a plain, elegant dance, just stepping, moving and turning with the music, and both the men and the spectators (and the poor birds for that matter) seemed subdued, even reverent.

STICKING YOUR NECK OUT

By

this time, I'd had several beers and probably five or six tequilas. I

was honestly beginning to believe that the people I'd been trying to

converse with could understand me and vice versa. While waxing more and

more “fluent,” I looked up and suddenly there was a turkey in my

arms. Apparently one of the men had singled me out as the "elder" of our

group. Before I could object, I was being pushed by the crowd out on

the dance floor and did the only thing I could: I danced with a turkey.

With the sensation of the warm, damp feathers on my hands

and arms, I let the both the music and my emotions move me

around the floor.

and arms, I let the both the music and my emotions move me

around the floor.

|

| ILLUSTRATION: Katy Farina |

The bird was surprisingly docile, given what must have been, for him, the otherworldliness of the situation. There I was, with the other three men, being watched by half the village, and the reality of the situation broke through the fog in which the tequila had shrouded me. While I was very much in the moment with the sensation of the warm, damp feathers on my hands and arms, I also felt a transcendent sense of peace and contentment as I let the both the music and my emotions move me around the floor. Then a very conscious thought rose through the raw motion: a prayer that I would never forget this magical moment.

Eventually, the loud music and less serene dancing returned, and the turkeys disappeared. A few minutes later, four young men crossed the dance floor, unceremoniously carrying the now limp bodies of the big birds by their necks. But, since everyone already had eaten dinner, I was left wondering what became of them. Still in my reverie, I never thought to ask.

TO SLEEP, PERCHANCE...

After

the turkey dance, people seemed to look at me differently, with

approving smiles, I thought. I did my best to engage in small talk, but

couldn't make out much of what they said above the thunderous music and

my re-thickening fog of inebriation.About midnight, we decided that, after such a long day, we'd find the hotel Silverio had booked for us along the road back to Puebla. But one of the wedding couple's relatives wouldn't hear of it, insisting we stay at his home. So we got our bags from the van and ambled off with him down the street. The music abated long enough for an even noisier round of fireworks.

A deafening aerial bomb went off, rattling the few religious

trinkets decorating the walls.

trinkets decorating the walls.

The house was relatively nice compared with most of the working-class Mexican homes I'd seen, with several sparsely decorated, apparently unused, small bedrooms. Kip and I shared one of them. The beds were quite nice, with decent mattresses, but, as in so many Mexican homes, the room cringed under the harsh light of a single bare bulb.

Just as we'd settled in, turned out the light and closed our eyes, the music started again at the party, blasting as if it were coming from the next room. At the same instant a deafening aerial bomb went off, rattling the few religious trinkets decorating the walls. Kip and I both burst into laughter at the amazing experience...and the obvious futility of trying to sleep.

DANCING WITH TURKEYS – Spirits Take Wing at a Small-town Mexican Wedding (part one of two)

One Man's Wonder

Reclaiming Curiosity in a "Ho-hum" World

(from onemanswonder.com)

My wife and I have taken a couple of tour-type vacations. You know, the ones where a guide takes a whole group of you around on a big tour bus. This kind of trip has a few distinct advantages, but experiencing authentic, unscripted local culture is not one of them. Generally, you're steered to events that appear to be staged especially for tour groups and, uncannily, they always manage situate you so you can’t get back to the bus without a trip through the gift shop.

Traveling on one's own, especially if you can do so with someone who lives there, often proves richer and more memorable. For it’s one thing to witness the culture of a place and a people; it’s another to live it. It’s a rare opportunity, one that seldom occurs without a convergence of effort, connections, and timing. Oh, and sheer dumb luck.

* * *

FISH OUT OF WATER

FISH OUT OF WATERThe weather in Mexico City was sunny and clear, but for the usual blanket of brown smog pressing down on this, the sixth largest city in the world. It was clear enough, though, to see Popocatepetl, crowned with clouds. Popo, Mexico’s most active volcano, is only 45 miles away from the center of Mexico City and her 20 million inhabitants and about half as far from Puebla, with another two million. It is within striking distance of all of them, a cataclysm-in-the-making, since eruptive activity has occurred as recently as January, 2008.

I was traveling with my Mexican-American friend and Spanish tutor, Silverio, along with two of his other students, Anne and Kip.

Silverio’s friends, Ignacio (Nacho) and his wife Martha, picked us up in the van he’d rented for us for the week. We drove right from the airport about 80 miles southeast to the state of Puebla and the small village of Santiago Tenango de Reyes, where we were to attend the wedding fiesta for one of Nacho's friends.

We

three unusually tall, unusually pale norte- americanos) walked in to what

seemed only slight curiosity from the 100 or so locals.

As we drove into Santiago, we realized just how small a town it was—only about eight blocks long and maybe three or four wide. Its population couldn't have been more than a couple hundred. We parked the van and walked a couple blocks on nearly-deserted cobblestone streets before we came to a broad alley between two cinder block buildings. There the stark space had been converted into a cheery hall by a huge bright yellow-and-green-striped tarp strung between the second stories above.

The six of us (Silverio, Nacho, Martha and we three unusually tall, unusually pale norte- americanos) walked in to what seemed only slight curiosity from the 100 or so locals—evidently half the folks in town—sitting at long rented tables. Within a minute, though, Nacho was proudly introducing us to the bride and groom (the groom Nacho’s co-worker in Mexico City), to the groom’s parents and to the couple’s padrino (something like a godfather). Pony beers and tequilas were in seemingly endless supply, and for the rest of the evening were cheerfully placed into whichever of our hands happened to be free at any time.

A ten-piece mariachi band dispensed its energetic music from the far end of the hall. The charro, or lead singer, is one of Nacho's cousins. Before I knew it, he was announcing something into the microphone about guests from far away and then something more familiar: “...por Cheff, de Meeny-sota…” Suddenly, I was aware that all the guests had now stopped talking and turned to look at us.

The next song, apparently just dedicated to me by Nacho, was Como Quien Pierde una Estrella (Like One Who Loses a Star), my favorite of the songs Silverio had taught us in class. I always love mariachi music, but I was especially moved by this rendition and Nacho's thoughtful gesture!

I kept wondering if I'd be so generous and thoughtful if roles were reversed.

After about an hour the parents of the groom asked us to join them. Leaving the other guests to their dinners, we walked about a block down the street to their home. Waiting for us inside were the bride and groom, still in their wedding finery, five or six other adult members of the immediate family and a few kids.

We sat down at the dining room table and were served what Silverio explained is a sort of appetizer course traditional for weddings: two types of tamales freshly steamed in corn leaves, two bright little gelatins which tasted like they might have been flavored by chiles, a sweet, crispy, deep-fried sort of cookie, and atole, a hot, creamy, corn-based drink flavored with chocolate, cinnamon or other notes.

It was already the experience of a lifetime just to attend the fiesta, but this—being welcomed like this into this dear family—made us feel deeply honored. I kept wondering if I'd be so generous and thoughtful if roles were reversed.

Leti's Restaurant

Best truck stop weather. It's handmade tortillas, fresh cheese, goat

stew, rubbed chicken and a cold beer. Letitia does it right!

Renting a car in Mexico: What you need to know

Christine

Delsol, Special to SFGate

Updated

9:00 p.m., Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Renting a

car in Mexico is much the same as renting in the United States, and you'll find

most of the major players Hertz, Avis, Alamo, Budget, Thrifty, et al. as well

as local companies, but navigating the country's notorious mandatory insurance

can take some careful research.

For the most part, bus travel is an

ideal way to get around in Mexico, but there are times when driving makes the

most sense. If you're on a tight schedule, you can cover more ground in less

time. If you're not on any schedule, you might want to explore and make up your

itinerary as you go. And even the second-class buses don't always cover every

place you want to visit. The Yucatan, for example, is especially suited to

driving: Many beaches, barely developed ruins and intriguing villages lie a

good distance from the main road. Highways are well-maintained, constantly

being improved, and so straight that the slightest curve bristles with warning

signs and reflectors.

Car rental: Easy, but with one big

"gotcha"

Arm yourself with some knowledge

about prevailing driving habits and road signs, and driving in Mexico is nowhere near as treacherous as

its reputation would have you believe. Renting a car is much the same as

renting in the United States, and you'll find most of the major players —

Hertz, Avis, Alamo, Budget, Thrifty, et al. — as well as local companies.

Similar rules and advice apply: You need a major credit card (or a boatload of

cash for deposit), driver's license and passport; book online at least a week

in advance for the best price; drivers under 25 pay more; airport pickups and

drop-offs cost about 10 percent more; always inspect the car with the agent to

mark every existing ding or scratch so you won't be charged for it, and check

to make sure the headlights and windshield wipers work as well.

Renting a car in Mexico has one big

"gotcha," though, and that is the minefield of the country's famously

mandatory insurance. Mexican car rental rates look wonderfully cheap on

comparison websites, but they don't include insurance, which can easily double,

and in some cases triple, the cost. Declining to buy the insurance (some of

which is mandatory, anyway) is foolhardy to the extreme, but buying the full

package without knowing what you're buying is only slightly less so.

Penetrating the insurance thicket

Mexican car rental companies offer

various levels of insurance, and only one is mandatory. Here are the basics

(costs listed are typical but variable):

Basic personal liability: Sometimes called third-party liability insurance, this is

the one, incontrovertibly mandatory insurance. It covers claims for injury or

damage you cause to another driver, car or other property damaged in an

accident, but it does not cover injury to you or damage to the rented vehicle.

Mexico does not accept liability coverage from U.S. auto policies or credit

card insurance. You simply cannot rent a car without buying Mexican liability

insurance. But here's what most renters don't know: By law, the mandatory

liability insurance is already included in the rental price. Cost: Included

in rental rate.

Supplemental liability insurance

(SAI): Sometimes called additional

liability insurance, this is not mandatory, though many rental companies will

tell you (or let you assume) it is. Still, it's worth considering. The basic

liability coverage is usually 50,000 pesos, or about $3,800, which won't go far

in anything beyond a fender-bender. Cost: $13 per day.

Loss damage waiver (LDW): Also called collision damage waiver (CDW) or LDW/CDW. This

is actually not insurance, but the rental agency's agreement to waive some of

the cost of theft or any damage you inflict on the rental vehicle. This one

requires some research and some careful thought. If your own auto policy or

credit-card insurance benefits cover collision damage, you can pass on LDW/CDW,

but keep some caveats in mind.

You are responsible to the rental

company for any loss or damage to the vehicle no matter what the cause is or

who is at fault. You will be detained until money matters are settled, and

if you lack liability coverage, your most memorable vacation sight could

include the inside of a Mexican jail until you pay off your obligation. Before

you decline LDW/CDW, verify that your auto policy or credit card insurance is

valid for rentals in Mexico, and that it includes loss of use. To collect on

your credit-card insurance, you must use that card when you rent the car and

when you pay the final bill. Carry proof of coverage with you, though rental

companies don't always require it. You must also explicitly decline the offered

insurance, which is not possible with companies such as Avis or National, which

include LDW/CDW in their rates or bundle it with the required liability.

Besides saving a bundle, your deductible

will be limited to the amount stated in your personal policy — credit card

insurance often has no deductible — while the rental agency's LDW/CDW insurance

usually carries a deductible equal to 10 to 20 percent of the vehicle's value.

(Many offer a deductible reduction or complete coverage option, which will add

$15 to $35 a day to the cost.) On the down side, some rental companies put a

hold on your card for the amount of the deductible. And in case of an accident,

you will have to carry the full cost of damages on your credit card until your

bank reimburses you, so you will need a hefty credit limit. And your insurance

won't cover every situation; clauses excluding damage to cars driven off-road

have been used to deny a claim for a car damaged in a dirt parking lot. Read

the exclusions carefully. Read them twice.

It can also take longer to sort

things out if you don't have insurance purchased by the rental car agency. A

few years ago, I bought full coverage because I had just changed credit cards

and insurance carriers and hadn't had time to research my coverage in Mexico.

My rental car was later smashed to bits by a drunken driver on the street in

front of my hotel. I filled out a police report in the morning, called the

rental agency, and was on my way in a new car 90 minutes later. It might have

been worth a delay and some additional paperwork to save the money if I'd known

I was covered, but it's one factor you have to weigh. Cost: $15 a day.

Personal accident insurance (PAI): Neither the included nor the supplemental liability

insurance covers injury to you or your passengers. This optional insurance

does, including ambulance, doctors and hospital. This might be covered by your

health insurance — again, verify — and it is not required. Cost: $4-$7 a

day.

Good to know

—Mexico's Secretary of Communication

and Transportation offers an excellent online "Point-to-Point Routes" tool that can make the difference

between an itinerary that works and one that messes up your entire vacation.

Select your starting and ending points, add some intermediate stops if you

like, and click "Find Route" at the bottom of the page. The map where

your best route appears is a bit clunky; the real payoff is the detailed

itinerary showing distances, driving times (evidently Mexican driver times; I

always add 10 to 15 percent), toll fees and estimated fuel costs.

—You'll rarely, if ever, find an

owner's manual in the glove box, so ask the stupid questions before getting

behind wheel: What makes the car alarm go off, and how do you stop it? Any tricks

to removing the key from the ignition? How do you put the car into reverse if

it's a manual? Add anything else that isn't obvious from a quick glance at

the dashboard.

—Make sure a copy of the insurance

policy is in the glove box and is up to date.

—If you book online, print out the

confirmation and show it when you pick up your car to be sure they don't try to

charge you a higher rate.

—Try to get your rate quoted in

pesos. Prices quoted in dollars will be converted to pesos for payment, usually

at more than the going exchange rate.

—The rental agency will give you a

24-hour, toll-free number to call if you need help. U.S. cell phones often

can't dial Mexican toll-free numbers, so if you're traveling with your own

phone be sure you have a local number as well.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

SIZED.jpg)

.JPG)